Stories about "Ukrainian Nazis" were rare before 2014. Then they surged as Russia's plans faltered.

Hoaxlines • Aug 3, 2022

Findings

We examined the surge in content discussing “Ukraine” and “Nazi” in far-left, far-right, hyperpartisan, and conspiracy theory websites during the Russian invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022. The findings suggest that the increased coverage of Ukraine-Nazi stories coincided with key events in the Kremlin-orchestrated invasions in both years, including protests, escalations, and strategic maneuvers. These media outlets amplified false Kremlin narratives that likely sought to justify Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

In both 2014 and 2022, the surge in Ukraine-Nazi content coincided with key events related to Russian invasions and actions in Ukraine. The false narratives seemingly aimed to justify Russia’s aggression and actions.

The findings highlight the potential impact of media manipulation on public opinion and the justification of military actions. By amplifying false narratives, these outlets may contribute to the spread of misinformation, negatively affecting international relations and conflict resolution efforts. Additionally, the study underscores the importance of critically examining media content and providing accurate information to counter false narratives and misinformation.

Overview

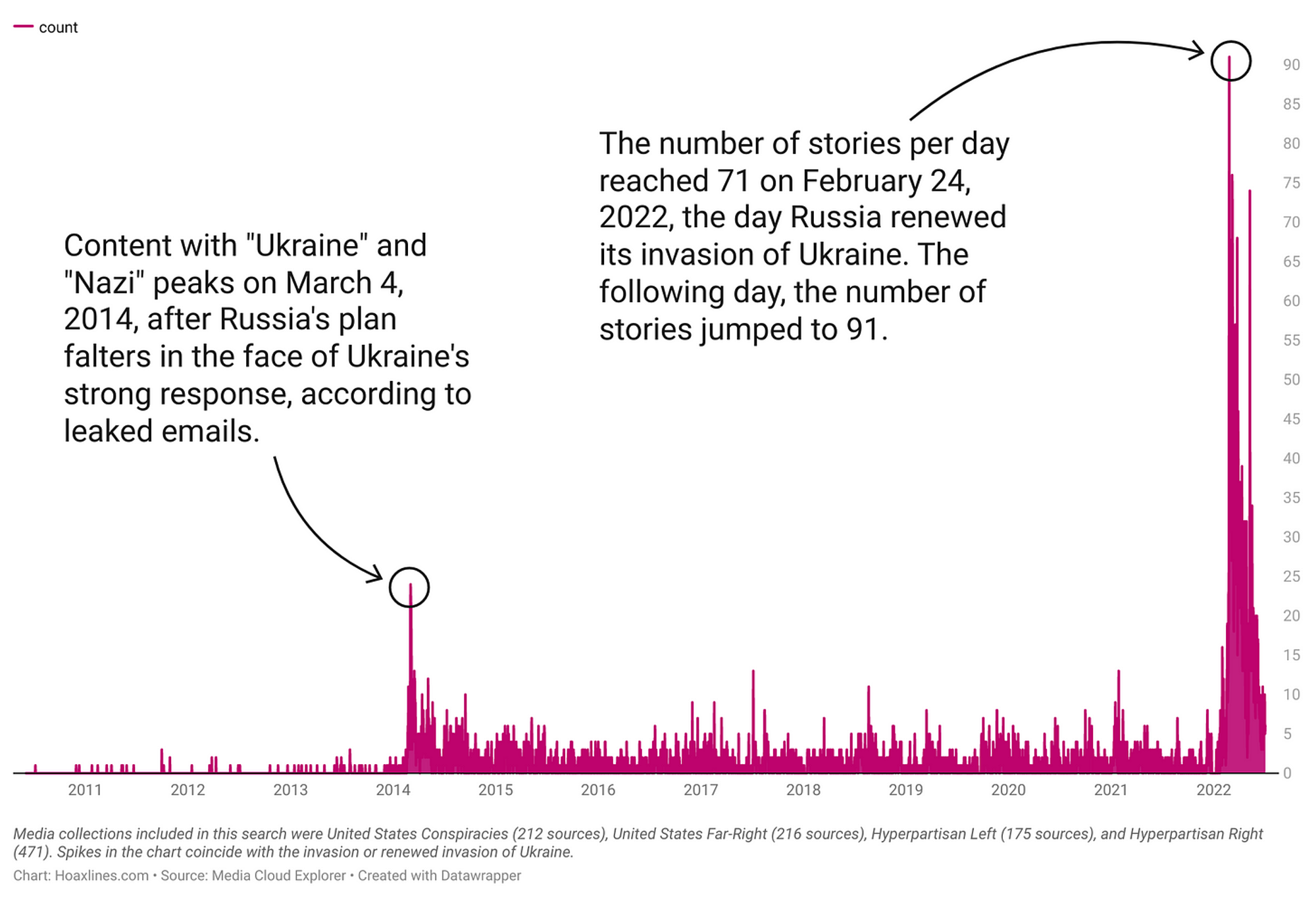

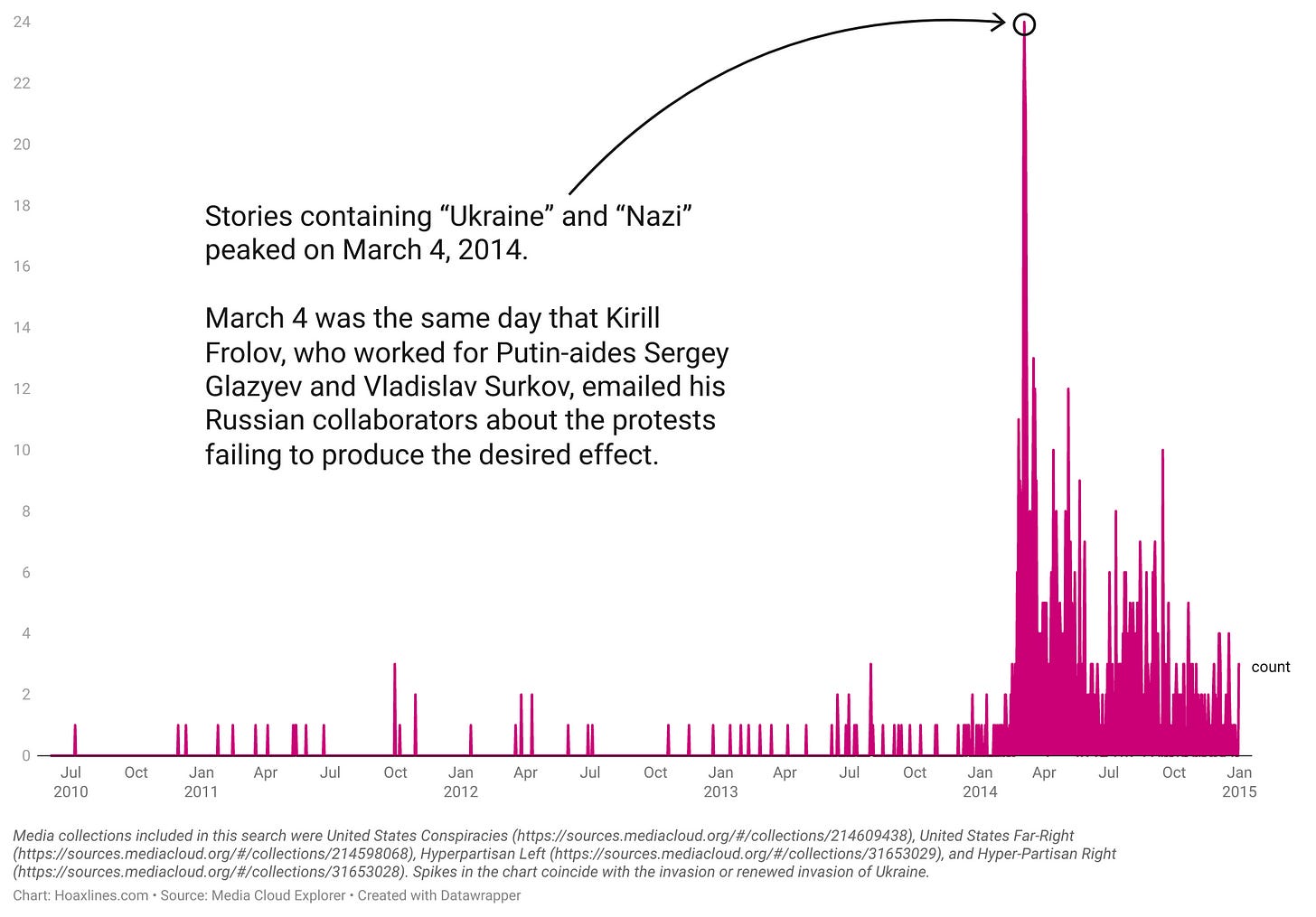

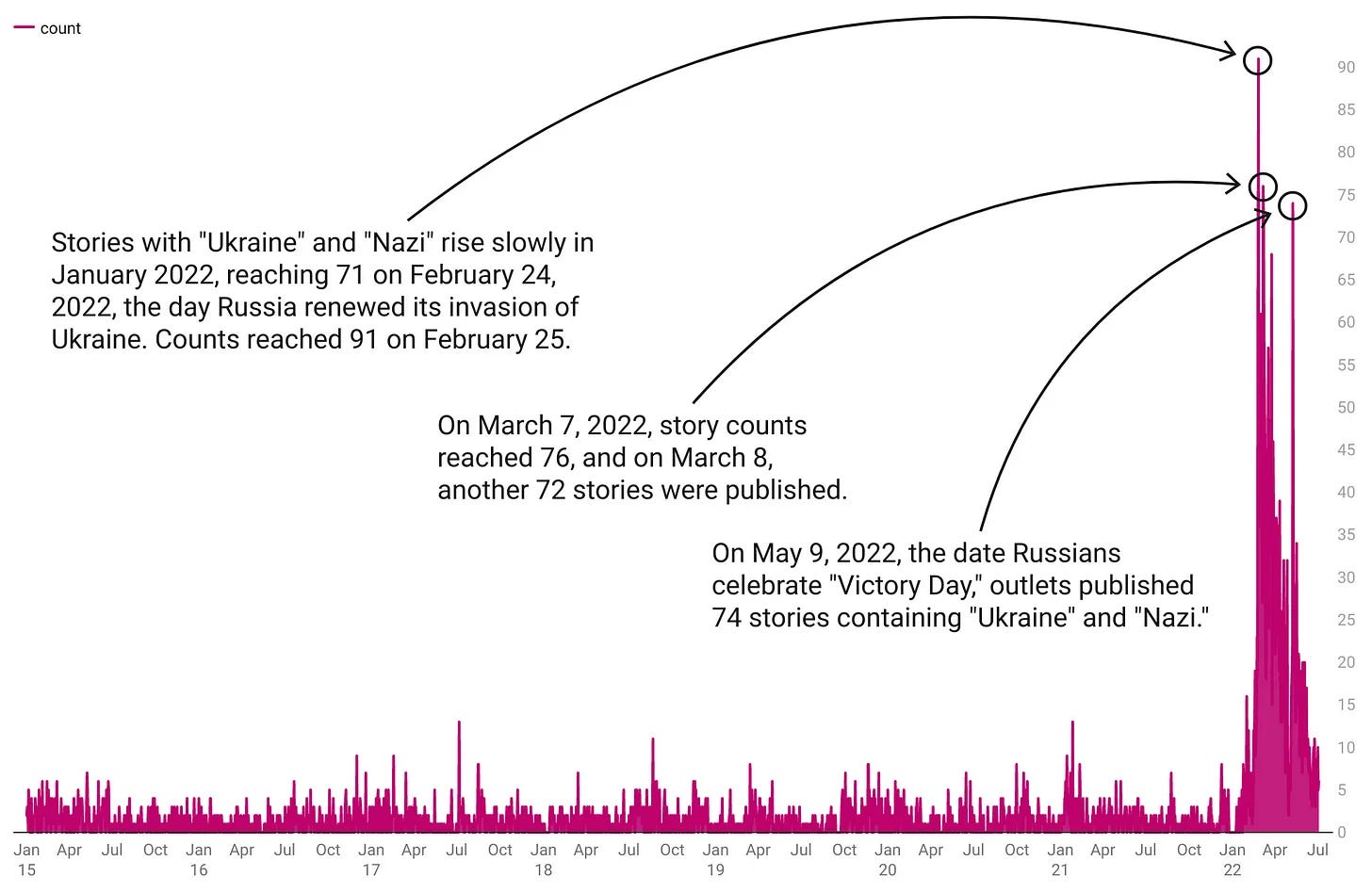

Hoaxlines gathered data to assess media discussions of “Ukraine” and the term “Nazi.” We searched across a decade from June 2010 through July 2022 using Media Cloud Explorer. We found that content discussing “Ukraine” and “Nazi” surged as the 2014 Kremlin-orchestrated events in Ukraine stumbled. The Ukraine-Nazi stories also increased before and coinciding with Russia’s February 2022 invasion.

We searched for the terms in outlets categorized as far-left, far-right, hyperpartisan, and conspiracy theory websites. Why and how these outlets ended up promoting false Kremlin narratives in 2014 and 2022 has received limited research interest but warrants examination.

Even to debunk the claims, outlets covering the subject risk contributing to media manipulation when they fail to provide critical information: Widespread concern about extremism in Ukraine was rare until Russia claimed Ukrainian extremism was its justification for seizing Ukrainian land.

Returning to the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine

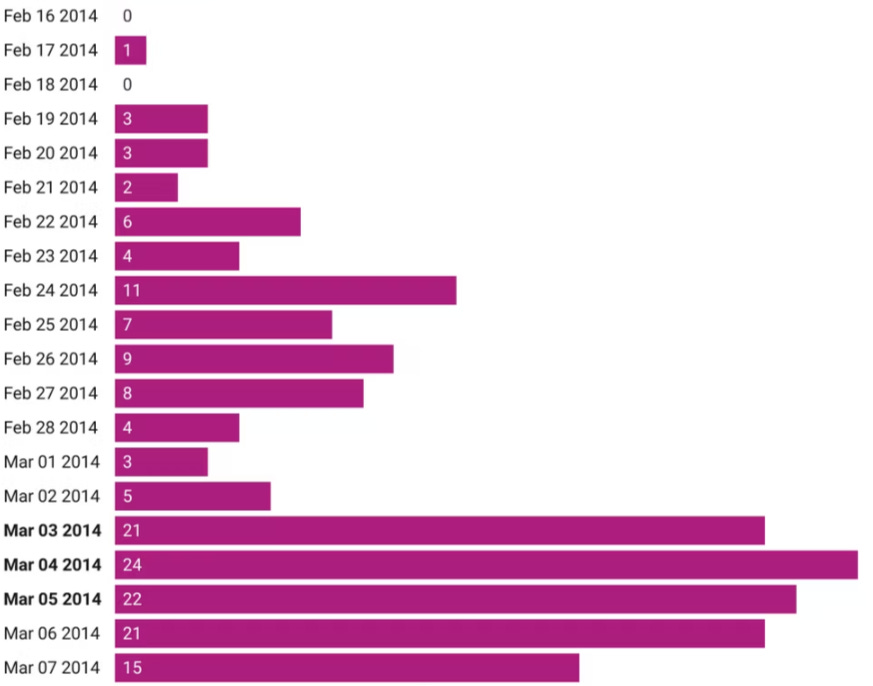

On March 1, 2014, the Russian parliament approved a troop deployment to Ukraine. By March 3, Kremlin-aligned groups had stormed the regional government building in Donetsk. The demonstrators demanded a split from Ukraine, but the protests had largely failed to produce the Kremlin’s desired effect, according to leaked emails from the time between Russian and pro-Russian actors.

The strong response from Ukrainian law enforcement had deterred pro-Russian figures who emailed collaborators inside of Russia to complain about their struggle. Western leaders condemned Russia’s actions in Ukraine on March 3, 2014.

At the height of the Ukraine-Nazi content surge on March 4, 2014, Putin claimed the military exercises were over. The following day, “Russian soldiers [blockaded] Ukrainian navy command ship Slavutych at the Crimean port of Sevastopol.” Putin scoffed at requests to remove Russian forces from Crimea, claiming they were not under his command.

Within days, an international voting observation team would be refused entry to Crimea with a warning shot. By April 2014, pro-Russian actors would seize the Regional Administration of Donetsk and declare it a “republic.”

In 2022, similar events unfolded, with denials that Russia intended to invade Ukraine. Russia followed its denials by renewing its invasion of Ukraine under the guise of a “Special Military Operation” on February 24, 2022.

Graphic timeline of Russian invasions versus the data

Content discussing “Ukraine” and “Nazi” surged as the 2014 Kremlin-orchestrated events in Ukraine faltered. The Ukraine-Nazi stories also increased preceding and coinciding with Russia’s February 2022 invasion.

The full bar graph timelines can be found here: Appendix for “Stories about "Ukrainian Nazis" were rare before 2014 when they surged at the moment when Russia's plans faltered.”

2014 data

- Content containing references to “Ukraine” and “Nazi” peaked on March 4, 2014.

- March 4, 2014, was the same day that Kirill Frolov, an analyst of the Institute of the CIS Countries who worked for Putin-aides Sergey Glazyev and Vladislav Surkov, complained about the protests failing to produce the desired effect in Ukraine.

2022 data

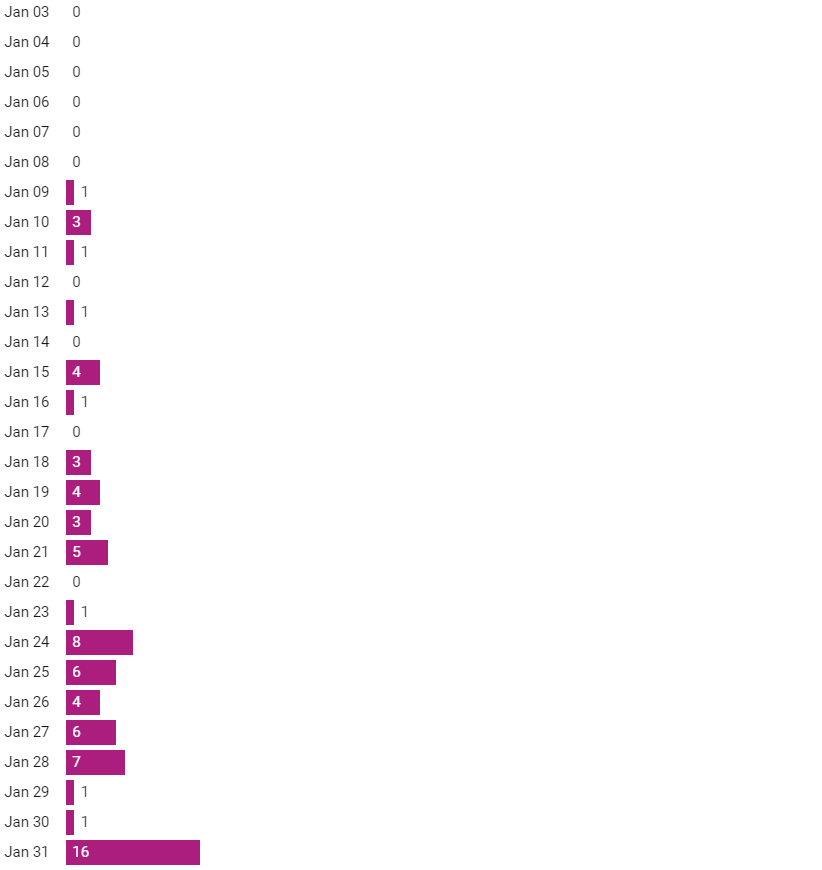

- Stories slowly increased in number throughout January 2022. Cyberattacks accompanied the increase.

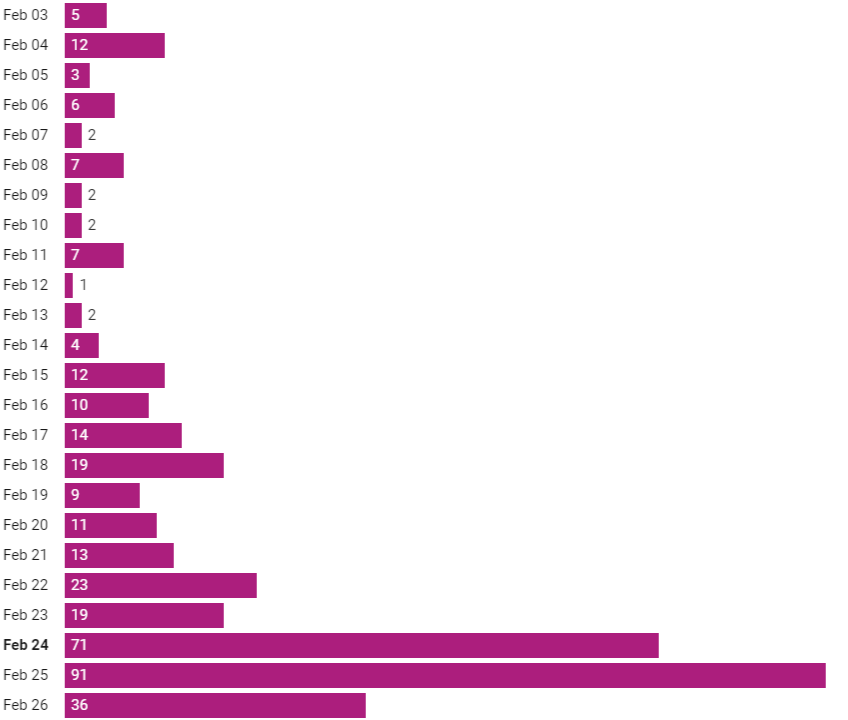

- The number of stories per day reached 71 on February 24, when Russia renewed its invasion of Ukraine. The following day, February 25, the number of stories reached 91.

- On March 7, story counts reached 76; on March 8, another 72 stories were published.

- Although possibly coincidental, on March 9, Russia bombed a maternity hospital, blaming Ukrainian “Nazis” for its actions. That same day, 58 stories containing “Ukraine” and “Nazi” were published.

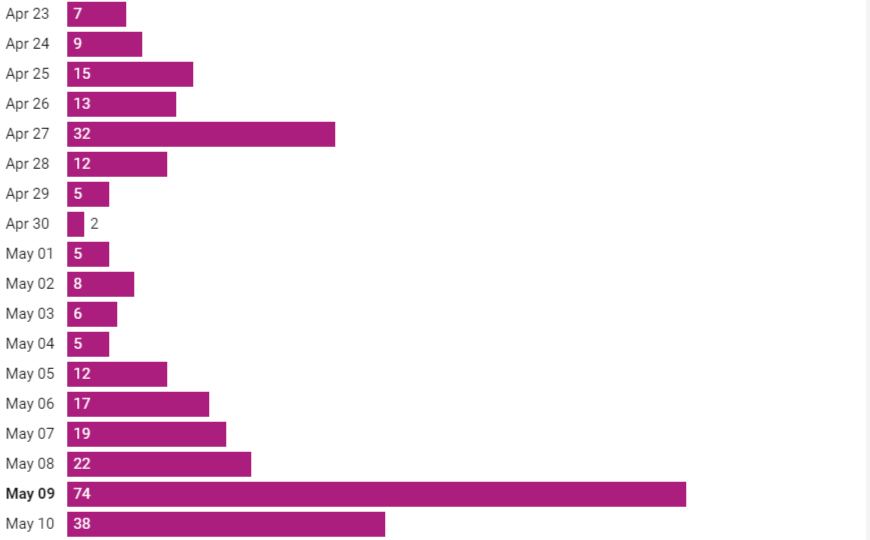

- On April 27, Russia cut off gas to Poland and Bulgaria in a move the European Commission called “blackmail.”

- Another important date was May 9. “Victory Day,” as the Russian government calls it, was the day Russia had hoped it would celebrate victory over Ukraine.

- On May 9, outlets published 74 pieces of content that matched our search criteria for “Ukraine” and “Nazi.”

What can the data tell?

The data suggest that concern about Ukraine and Nazi-related far-right extremism on hyperpartisan and conspiracy websites likely relates to Russian land seizures in Ukraine. Before the invasion, Ukraine had a marginal far-right presence. Stories containing the two search terms were negligible before the 2014 invasion.

The disinterest before the invasion is all the more noteworthy because Russia falsely claims its invasion intended to “liberate” Ukraine from “Nazis,” a process the Kremlin calls “denazification.”

In 2014, the strong response from Ukrainian law enforcement was a stumbling block for the Kremlin. But the tides seemed to turn after a flood of articles accusing Ukraine of being run by Nazis was unleashed online. The content peaked on March 4, 2014, the day that Putin claimed his military exercises were over.

Even with nationalist sentiments increasing in Ukraine after 2014, a far-right candidate on the 2019 national ballot received 1.5% of the vote. In this same election, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a Russian-speaking Ukrainian of Jewish heritage, won the presidential election in a “landslide victory.”

Reporting Radicalism wrote of the election in 2019:

The 2019 result was not unusual for Ukraine: in the 2010 election, Oleh Tyahnybok of the Svoboda party received 1.43 percent of the vote. In snap elections in 2014, Tyahnybok received 1.6 percent of the vote, while Dmytro Yarosh from the Right Sector party received 0.70 percent. These vote totals indicate that the risk of a right-wing authoritarian regime being established in Ukraine was and is extremely low.

For comparison, a far-right candidate on the ballot this past May in Georgia, U.S., received 3.4% of the vote.

The other notable increase in content happened in 2022, as Russia attempted another land seizure in Ukraine. The difference with the timing of the content in 2022 was that content surged at the same time the invasion began, rather than after the effort appeared to be failing in 2014.

Recommendations for media coverage

Globally, the threat of far-right extremism has risen in the past decade. It’s a threat Hoaxlines does not dismiss, even in Ukraine.

The concern about media reporting relates to the relative lack of interest before the Russian land seizures. That reality warrants acknowledgment in stories covering extremism in Ukraine. Stories failing to contextualize the scale of extremism in Ukraine compared to other democratic countries, in effect, further Russian propaganda.

NPR reported on Russia’s attempts to justify its actions in Ukraine in March 2022:

A lengthy list of historians signed a letter condemning the Russian government’s “cynical abuse of the term genocide, the memory of World War II and the Holocaust, and the equation of the Ukrainian state with the Nazi regime to justify its unprovoked aggression.”They pointed to a broader pattern of Russian propaganda frequently painting Ukraine’s elected leaders as “Nazis and fascists oppressing the local ethnic Russian population, which it claims needs to be liberated.”

And while Ukraine has right-wing extremists, they add, that does not justify Russia’s aggression and mischaracterization.

Ukrainian intelligence intercepted instructions for Russian intelligence agents that instructed how to cover the Russian “special military operation” in Ukraine. The instructions included orders to establish “networks of propagandists” to help shape a positive opinion about the actions of Russian troops in Ukraine. The orders complement other evidence about Kremlin planning surrounding its invasions of Ukraine, like leaked emails.

Hoaxlines assesses that the best way to avoid participating in media manipulation on this topic is to address, in the opening paragraph, how and when interest in the subject began and whose interests attention to the topic may serve. Examples of relevant details include comparing the level of extremism in Ukraine to other democratic countries and explicitly stating that domestic extremism—a problem found in nearly, if not all, countries today— does not justify Russia’s actions.

The media should be aware that outlets rapidly transmitting the preferred narratives of a foreign state could pose a dire threat to U.S. national security in many situations, but especially in public health emergencies.

How we gathered the data

Hoaxlines gathered data from Media Cloud to assess the content volume of articles discussing “Ukraine” and “Nazi” from June 2010 through July 2022. We searched for these terms, used together, in articles from outlets listed in one of four Media Cloud Explorer lists, United States Conspiracies, Hyperpartisan Left, Hyperpartisan Right, and United States Far Right.

A collection similar to the United States Far-Right list did not exist for the political left; however, the United States Conspiracies list contains outlets that might be considered far-left or far-right.

Researchers and journalists have observed a right-leaning bias among recent sources of low reliability, although that doesn’t consider the content volume produced by each website. Media bias charts also suggest this bias, so the unequal counts for websites are neither unexpected nor indicative of having omitted far-left websites.

You can find a live version of the graph here: Hyperpartisan and conspiracy theory website daily story counts for content with "Ukraine" and "Nazi" from 2010 to 2022.

Key events timeline

Re-published under the Open Parliament License from the U.K. House of Commons:

Source: Walker, N. Ukraine crisis: A timeline (2014 – present). In: House of Commons Library. 2022 [cited 3 Aug 2022].